It has been a year since the 18th Edition Wiring Regulations (BS 7671:2018) came into effect. While most of the changes appear to have gone smoothly, there are still questions around the use of arc fault detection devices (AFDDs).

Before we go into those, let’s review the basics…

The basics of AFDDs

AFDDs are circuit protection devices, like miniature circuit breakers (MCBs) and residual current devices (RCDs), although they offer a different type of protection. They are essentially microcomputers that sit with an overcurrent protective device, though they can be combined. They are designed to look for the signature of an electrical arc. Upon detecting this signature using complex algorithms, the device will operate.

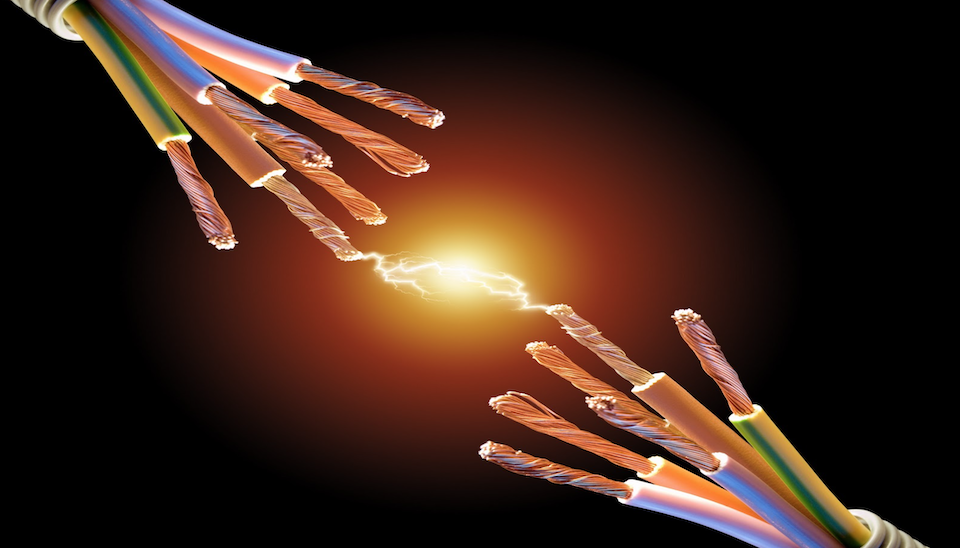

For ‘arc’, you can read ‘spark’ – from a small fault in a circuit between two live conductors or live conductors to earth. These are usually caused by damaged cables, loose connections or some other breakdown in insulation, and they can generate enough heat to start a fire.

Pre-existing devices which are mandatory in the Wiring Regulations – circuit breakers, fuses and residual current devices – may not always respond to the small arc faults which would activate an AFDD.

Assessing the benefits

Firstly, AFDDs carry many benefits. For one, they provide protection where other devices cannot. Government statistics show that, in 2016/17, there were more than 13,000 fires in England which occurred in electrical distribution and other electrical appliances. Although there is no direct evidence to suggest these were directly caused by electrical arcs (and such evidence can be hard to find), it is sensible to suggest that AFDDs could help to lower these figures.

On the other hand, while they provide a great supplement to a full life protection system, AFDDs are not perfect. The require a minimum load, take up additional space in boards which most likely will not have been designed to accommodate them, and they may not detect all potential faults on ring final circuits.

Also, they are not updateable – as mentioned above, AFDDs are essentially microcomputers with a rudimentary ‘operating system’ – so they may become outdated by newer models.

Are AFDDs mandatory?

AFDDs are not mandatory – at least not yet. The devices have been around the industry for some time but only rarely used. The 18th Edition has highlighted these devices by recommending their use – but the key word here is ‘recommending’. As such, the Regulations leave the choice to use them down to the designer of the installation.

The designer will therefore have a few points to consider before committing to a design decision, such as:

• Worthiness of the perceived additional protection offered.

• Possibility and consequences of ‘nuisance tripping’.

• Practicality of installing such devices – particularly regarding switchgear enclosure size.

• Any requirements imposed by device manufacturer regards testing and maintenance.

• Costs – which can quickly escalate as AFFDs are usually needed on each circuit and they can be expensive (of course cost is not to be considered against safety).

• Potential future design liability.

Best practice

A good-practice risk assessment approach for AFFD usage should equally weigh the pros and cons of adding AFDDs to a life protection system (a full set of devices including RCDs, MCBs, surge protection devices and others, designed to make installations as safe as possible). Cost alone should never be the overriding factor – any good designer should always put safety first.

Equally, a good risk assessment should have considerable input from an electrically skilled person as well as the client or end user. AFDD inclusion should be considered as part of an overall fire protection strategy and their limitations should be considered and discussed with the client beforehand.

AFDDs can certainly be of benefit to some installations. However, they are not to be considered as the only protection measures. They can be added to existing protective measure where their benefit is clear, but they must be carefully considered, lest an installation become over-engineered.